Now Magazine Toronto Cover Story

NOW MAGAZINE TORONTO

Local brat’s

mind-blowing paper-and-ink works have strange powers

NOW MAGAZINE TORONTO: In the dark apartment where artist Mike Parsons creates his ink-on-paper art, a huge drawing sprawls across a large table. It’s flecked with stills from a cartoon he’s in the process of animating. His childhood friend, Hans Finkledey, huddles over a series of switches and effects pedals, mutating sounds from the radio into a barren soundtrack for the piece. In the cartoon, a man sits alone, contemplating a noose for a moment before hanging himself and flying out of the frame. The process repeats itself every 12 seconds. Small cells create a living border around him, and in them fiery buildings rise and fall, bombs swirl, coffins empty and skeletons overrun the land.

I tell Parsons the work is dark. He tells me that in every piece shines a light.

"The thing with these is that they do show agony and torment, but in the smallest places I put people fishing or talking," he explains in a quiet, even voice.

"A lot of people look at it and go, "Whoa, this is just evil.’ But if you actually take the time to sift through it you can find the nice parts."

He pauses for a second, as if coming to a realization for the first time. "I guess that’s kind of like life."

Sometimes it seems that history bends its course to follow the work of Mike Parsons.

It’s hard not to read his jet-black ink drawings as depictions of the collapse of the World Trade Center towers or the inevitable bombing of Iraq.

But Parsons rendered his images in black-and-white long before they were funnelled to our television screens in full colour. The Scarborough native began drawing disintegrating buildings almost a year before September 11. He wanted to reflect the unsustainability of modern living.

NOW Magazine Toronto |

"When I started doing these, there were no buildings blowing up," he says, gesturing to the huge images depicting black buildings melting into each other. He then turns toward a series of pictures that show bombs plunging into chaotic cityscapes. "When I started doing these, they weren’t talking about bombing Iraq." He renders images of overcrowding, violence and loneliness in vivid black inks, his messy, disordered style blending with the dark tone of the work. "It’s basic black-and-white. It’s ink on paper. It’s as simple as you can get. I think my ideas and my art are simple." Simple -- and truly unsettling. His is a world where monsters do exist. He refers to himself as a subversive cartoonist. Perhaps because of his comic-book style, children like his drawings. "All the little kids in the neighbourhood love the big monsters. They come out and dance on them," he says, referring to monsters he painted on the sidewalks in front of the Ontario College of Art & Design, where he is currently finishing his studies. You can still see a long row of primitive monster faces along the back construction wall at the school, bordering Grange Park. "The mural is behind the kids’ playground, so they love that, too. Someone went and added genitals and nipples to the drawings." He pauses for a moment as if wishing them away. "That wasn’t necessary." |

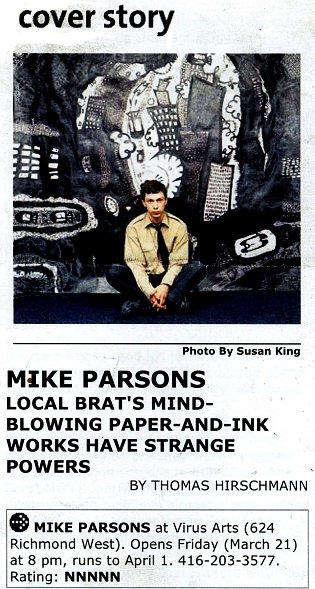

Parsons seems barely beyond childhood himself. He’s 25, but his small frame and youthful face make him look barely out of high school. He’s usually optimistic, seeming to occupy a happy place somewhere between childhood exuberance and aged wisdom. And he’s extremely polite -- the kind of young man any mother would be proud to call son.

But every so often the harder edge you see in his work bleeds through into conversation: an aggressive tone, a frustrated word, a comment about the harshness of the world. He says he’s less angry at the world now than he was before September 11.

"I’m more relaxed these days. I don’t read as many books. And I don’t have television. I record a few cartoons when I go home to visit my mom, but that’s about it. No CNN." When I meet him at OCAD one evening, he wears his customary black tie, black shirt, black sweater and black pants. He tells me how much he likes the colour red.

So much, in fact, that he brought a can of red paint to school one day and began painting a corridor red. The other students joined in, and soon the mundane white walls were teeming with rich red colour.

"The other students were really excited," he recalls.

The hall monitors weren’t so enthusiastic. They gave him a can of white paint and forced him to repaint.

"You can still see some of the red here, and a bit here, where I didn’t cover it up so well," he says, pointing to red paint that’s retreated into the walls’ cracks and corners.

With the leftover paint, he scrawled the word "boring" across dozens of the school’s surfaces. It’s difficult to see the words, as they’re painted white against white.

"In the light you can see all these "boring’ white walls in the school," he says with a chuckle, trying to be cool but obviously a bit proud of his rebellion. "I’ve seen them try to paint over some, but it’s not much use. There are so many." He shows me remnants of other pieces he’s taped up around OCAD and tells me about others that no longer exist.

His talent for creating vivid work is matched by his prolific -- bordering on obsessive -- output.

He began drawing in coffee shops in Scarborough, and says he now rarely stops. He draws six to eight hours a day. He makes large numbers of smaller pieces, and from time to time works ink into paper the size of a king-sized blanket. He even takes notes in his philosophy classes by drawing pictures of the ideas. For his upcoming show at Virus Arts -- opening Friday (March 21) -- he plans to hang more than 750 drawings.

But there’s a cost. He’s suffering from the repetitive strain of making the same motions over and over again, day after day.

"I’ve been having serious problems with my hand. Becoming left-handed was good. Several times when my right hand just went, I could keep going with my left. I tried my mouth and feet, but that wasn’t too good." Now he uses both hands to keep up the pace.

"Almost all of the borders were done with my left hand. That gives me rest time. I’ll do 20 or 30 of these and then go in with my right hand and do the detail stuff." He fantasizes about recruiting an army of assistants to help him execute his visions should he ever lose his hands altogether.

"I don’t know how to do anything else but draw."

NOW MAGAZINE TORONTO By THOMAS HIRSCHMANN

This feature article appeared as the Now Magazine Toronto Cover Story in March 2004 and on the NOW Magazine Toronto website.